It has been more than a decade since Coffee Review explored Costa Rica coffees in depth, though we cup many individual samples each year from this small, coffee-celebrated Central American country. In the last year alone, we reviewed 26 Costa Rica coffees at ratings of 91 to 96, including one, Temple Coffee’s Costa Rica Alberto Guardia Venecia Honey (94), which landed at the #17 spot on our 2015 Top 30 Coffees list.

The story of Costa Rica coffee over the past several years is one of nimble, innovative response to profound changes in the high-end specialty coffee market. Historically, Costa Rican coffee farmers took their fruit to large, centralized mills for processing. Growing elevations were usually high, so the cup was bright and substantial in mouthfeel. Tree varieties were classic, though not particularly distinctive in the cup. The centralized mills generally did an impeccable job of wet-processing the fruit. All of this added up to the admired but predictable Costa Rica cup of recent tradition: clean, bright, dependable, though not particularly distinctive or striking. Coffees were typically sold by exporters by growing region and grade.

The Rise of the Micro-Mill

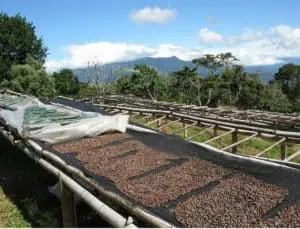

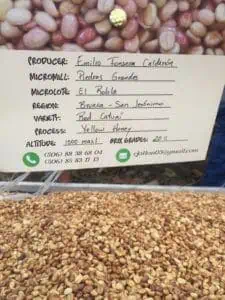

Over the past few years, all of that has begun to change dramatically in the direction of traceability, sustainability, and, most impressively, product diversity. The main vehicle of this change has been the evolution of the micro-mill. In Costa Rica a micro-mill is, essentially, a farm that also has its own processing equipment on-site, allowing farmers to maintain oversight during every step of primary processing and drying, rather than sending their coffee fruit to a large mill where it will be processed, bulked and sold by region, grade or exporter brand. Consequently, farmers can separate coffees by lot, based on different tree varieties and processing methods, and engage in direct relationships with buyers, tailoring their processing choices to buyer interest.

For example, when I visited the Urena Rojas family’s farm, Café Rivense del Chirripó, during harvest this past January, I learned that nearly half of the farm’s production had been purchased by buyers in Asian markets specifically to be processed in a variety of honey methods. (More on Costa Rican honey-processing below.) The farm’s on-site mill offers the family the ability to process coffee (wet-processed or in a range of honey and natural processing styles) by individual lot or custom blends of coffee varieties, including micro-lots grown for buyers with whom the farm has established long-term relationships. One of the coffees we review here, Camino Real’s Café Rivense El Mango (92), was processed by the black honey method on this farm.

Building a micro-mill from scratch can cost a farmer upwards of $50,000, a costly investment for many Costa Rican farmers, but the premium these farmers can now obtain for their micro-milled green coffee may be as high as $0.40 per pound, making the investment a sound one. Banks are now willing to loan money to farmers to support this new model, which contributes to its further development. As of this writing, there are 147 micro-mills in Costa Rica, and that number is growing, constituting a trend often described as the “micro-mill revolution,” a term coined by exporter Francisco Mena of Exclusive Coffees.

Micro-Mills and Terroir

Another consequence of the emergence of micro-mills is the industry’s ability to better embody potential differences among the terroirs of Costa Rica’s diverse coffee-growing regions. “Terroir” is a term often associated with wine grapes, but it certainly applies to coffee trees as well, as it invites us to characterize coffees based on the environments in which they’re grown, taking into account altitude, soil type, weather, and other important factors that affect acidity, flavor and overall cup character. Unfortunately, aside from growing elevation, which clearly promotes bean density and acidy brightness, and dry harvest seasons, which generally help promote sweetness, not much is known for certain about the detailed impact of terroir on the sensory properties of coffee, although certainly the traceability promoted by the micro-mill movement supports the eventual gathering of that knowledge.

There are eight primary growing regions identified by ICAFE (the Costa Rica Coffee Institute), the public, non-governmental institution established in 1932 to promote Costa Rica coffee: Central Valley, Tres Ríos, Turrialba, Brunca, Guanacaste, Tarrazú, Orosi and West Valley. Of the 13 coffees we review here, all are from Central Valley, Tarrazú, West Valley and Brunca.

Traceability and Sustainability

Environmental sustainability, which has been a buzz word, especially in the U.S. and Europe, for some time, is becoming a serious issue throughout the coffee supply chain as global warming makes its dangers more visible each year. True environmental sustainability can be achieved only through a rigorous traceability protocol, as it guarantees that certain production methods, such as low water use and recycling of waste, are complied with. ICAFE is the independent body that oversees compliance in Costa Rica.

Every coffee mill in the country must comply with seven laws and four national decrees governing restrictions on water use, hydrocarbon production and wildlife protection. Many of Costa Rica’s coffees are described as being “eco-pulped,” which ICAFE’s Promotion and Projects Director Mario Arroyo describes as a mechanical demucilaging system that reduces water usage and requires treatment of the waste products as well.

True, the use of the eco-pulper, which squeezes and scrubs the sticky fruit pulp or flesh off the beans rather than removing it by the traditional method of fermentation and washing (both sources of pollution unless waste water is treated), was not greeted with unmitigated joy by most high-end specialty roasters in consuming countries. Their position was that mechanical demucilaging or eco-pulping does not thoroughly remove the fruit flesh, and, by eliminating the traditional ferment step, it encourages a standardized or simplified cup profile. In Costa Rica, however, the leaders of the micro-mill movement have turned these supposed limitations of the eco-pulper into positives by learning how to calibrate the machine to remove various percentages of the fruit flesh before drying the beans, thus deliberately varying cup profile and creating today’s “honey” styles of coffee. In other words, they turned eco-pulping from a potentially cup-simplifying negative into a cup-expressive positive.

The Sun-Growing Challenge

More on the honey system below. But to return for a moment to the theme of coffee and sustainability, the flip side of the sustainability coin in Costa Rica is that more than 90% of Costa Rica’s coffee is grown in more-or-less full sun, rather than in mixed-species shade, the traditional system in Central America. Costa Rican farms are planted mainly in the Caturra, Catuai and Catimor varieties of Arabica, all sun-tolerant but often considered less distinctive in the cup than many traditional shade-grown varieties, Bourbon in particular.

These sun-tolerant varieties allow for denser plantings and higher yields, but increase the need for chemical inputs and discourage the ecological diversity associated with mixed species shade, a practice that attracts birds and insects to the coffee fields and promotes a more stable, sustainable ecology. This will not be an easy problem for Costa Rican coffee leaders to address. However, despite a trend away from shade-grown coffee, Costa Rica is the first tropical country in the world, according to a 2012 World Bank report, to reverse deforestation, up to 51% forest in 2010 from a low of 35% in 1980. This is largely owing to the country’s 17-year ban on clearing mature forests.

Joining in a Surge of Global Coffee Innovation

The unmitigated good news is that the ingenious use of mechanical demucilaging to create new coffee types has allowed Costa Rican coffee farmers to join in the eruption of creativity and innovation that has recently transformed the international coffee specialty scene. Although still largely stuck with plain-tasting tree varieties, Costa Rican farmer-millers have compensated by playing the processing card with particular innovation and determination. True, producers in many countries also are busily departing from the traditional ferment-and-wash processing that has been associated with fine coffee for the past hundred years. Producers almost everywhere are offering coffees dried in the entire fruit (“natural” processed), as well as variations on the honey-processed coffees described here.

But no country has varied and refined these methods with quite the enthusiasm Costa Rican producers have. According to Arroyo, not only do local farmers produce white, yellow, red and black honey coffees, but they also offer their buyers differentiation among natural-processed coffees by further distinguishing them as “heavy,” “smooth” or “normal.” This is in addition to traditional ferment-and-washed coffees, plus a processing refinement some Costa Rican producers call “double-washing,” apparently meaning that after the removal of fruit flesh by mechanical demucilaging the beans are immersed for 24 hours in clean water to soak off the last remnants of fruit flesh.

Names or Innovations?

This last procedure–soaking the beans in clean water after washing or demucilaging–is a common practice in many growing countries, but the producers in Costa Rica have given it a name, as they have given names to the approximately ten different processing refinements discussed here.

While this tendency to create names might make these variations appear more like marketing exercises than actual coffee innovations, ICAFE in fact has gathered data on differences among, and best practices for, each of the various named processes, all of which have become relatively standardized over time; to wit, percentages of fruit flesh left on the bean are defined for each honey type as follows: white honey retains 25% of the mucilage or “honey” during the de-pulping process, yellow honey, 50%, and red honey, 100%. Black honey coffees also retain 100% of their mucilage during the drying process, but are dried over longer periods than red honey, typically resulting in a different, often slightly fermenty, cup.

Natural-processed coffees are dried as whole fruit, of course, and typically over longer periods of time than any of the preceding styles of honey-processed beans. Precise parameters for the various styles of natural are dependent on specific drying practices and on weather.

Buyer Preferences and the Costa Rican Processing Styles

Over the past few years of cupping Costa Ricas at Coffee Review we have confirmed general cup tendencies of all of these coffee types, although we would emphasize that we have identified tendencies only, not predictable certainties. Without a doubt the less fruit allowed to remain on the bean during drying (washed, white honey, yellow honey) the more tendency to clarity and brightness in the cup, and the more left on the bean (red honey, black honey, naturals) the less predictable the relationship of processing method to cup becomes, with a wide array of tendencies possible. For examples of some of these tendencies, see the last part of this report and associated reviews.

According to Wayner Jimenez, Quality Control Manager of Exclusive Coffees, a Costa Rican coffee exporter, current buyer preferences—presumably among his company’s green coffee-buyer customers—run heavily in favor of white and yellow honey preparation (80% preference), with little interest in more conventional washed coffees (1% preference) or naturals (approximately 4% preference). Red honey registers 10% preference and black honey 5%.

All that these figures may mean is that buyers look for conventional washed coffees or full natural coffees elsewhere, and are coming to Exclusive Coffees for what has become a Costa Rican specialty, a range of refined honey coffees.

The Coffee Review Experience with Costa Rica Processing Styles

Certainly based on number of submissions representing these various Costa Rica coffee types that show up for review at our lab, roasters appear to be about equally interested in Costa Rica honey-processed coffees, natural-processed coffees, and more conventional washed coffees. In 2016, among the 26 high-rated Costa Rica coffees we reviewed, eight were honey-processed, seven natural-processed, and seven “washed” coffees (which could mean either traditionally fermented-and-washed or eco-pulped with the machine set for full removal of mucilage). Processing method for four of the 26 samples we reviewed was not specified.

The Coffees

We cupped 36 coffees for this article. Scores ranged from 83 to 94, with an average of 90. We review the top 13 here, all of which scored between 92 and 94. Of these 13, three are washed (one “double-washed”), four are natural-processed, one is white honey, two yellow honey, and three black honey.

This variety in processing among coffees scoring at the high end of this month’s testing speaks to the success of these multiple methods and their distinct approaches. We found that the naturals and black honeys, in general, either appealed in their delicate fruit-forwardness or were a bit overly fermenty and heavyish. Two of the black honeys reviewed here, Magnolia Coffee’s Don Pepe (93) and Kéan Coffee’s Sonora Colorado (92) were boldly fruit-centered, but also alive with floral and sweet spice notes. The third, Camino Real’s Café Rivense El Mango (92), which was slightly darker-roasted than the preceding pair, was deeply chocolaty, with black cherry and caramel undertones. The naturals, which include the Corvus Las Lajas Perla Negra Natural (94), Temple’s Costa Rica Alberto Guardia Bourbon (93), a high-scoring coffee over the past several years, Willoughby’s Sumava Caturra (93), and Argyle’s Las Cuadras F1 Hybrid (92), all displayed an elegant fruit balanced with notes of chocolate and citrus zest, and in some cases a tamarind-like sweet-tartness.

The three yellow and white honeys, not surprisingly, resembled more closely the style of the two washed and one double-washed coffees also reviewed here, displaying sweet floral notes and clean, though often lush, fruit suggestions.

Adam Pesce, Director of Coffee at Reunion Island in southern Ontario (whose Sol Naciente is review here at 92), explains Costa Rica’s appeal: “Ever since Costa Rica developed the micro-mill model, their [best] coffees have gone from good to great. Honey coffees are particularly crowd-pleasing—the sweetness that comes from the processing and the balance that you commonly find in Costas match up so well together.”

The Costa Rican micro-mill movement is ultimately a tribute to coffee’s newfound creativity and innovation in the face of coffee’s 21st century challenges. Confronted with an apparent constraint on coffee tradition imposed by society’s legitimate ecological concerns, Costa Rican growers have found a way to turn that constraint into what is probably the first chapter of an exuberant, still-evolving explosion of local coffee innovation, innovation that proceeds from the logic of coffee production itself and which offers through its rich and explicit processing language a way for consumers to participate in the vibrant experiments now taking place at Costa Rican farms and mills.