Four burr coffee grinders, from left to right: Oxo Conical Burr Grinder With Integrated Scale, Baratza Virtuoso+, Breville Smart Grinder Pro, and KitchenAid Burr Grinder. Photo by Howard Bryman.

Grinding whole beans immediately before brewing is one of the single most powerful upgrades you can make to the quality of the cup you brew at home. No matter what grinder you own, it’s better than owning no grinder at all. Yet when examining the differences from one coffee grinder to the next, and contemplating the sheer variety of products available on the market, it quickly becomes clear that what we ask grinders to do, and evaluating how well they do it, is neither simple nor easy.

For this report, Coffee Review thoroughly tested four popular burr coffee grinders: the Baratza Virtuoso+, the Breville Smart Grinder Pro, the KitchenAid Burr Grinder, and the Oxo Conical Burr Grinder With Integrated Scale. The MSRP for these grinders currently ranges from around $200 to $270. From our point of view and our general experience, grinders in this price range and class have the potential to represent a reasonable balance between quality and affordability for a lover of fine coffee. They tend to perform best for brewed coffee – drip, French press, AeroPress, and various immersion methods. Some also can be used for espresso brewing (see the individual reviews), although a specialized espresso grinder is generally best for that demanding method.

Reviews of each machine can be found by clicking on the grinder names in the preceding paragraph, but to understand what we were looking for and what sets machines apart, in general, it helps to first understand what happens when beans are passing through any grinder, and then what it is we want from the grounds that come out.

The Journey from Beans to Grounds

Coffee beans are dense, brittle little packages. When a bean comes in contact with a grinder’s burrs or blades, it doesn’t get sliced like a melon or even chopped like a nut. Coffee beans tend to explode upon impact, resulting in an array of what we call boulders and fines, meaning big chunks of bean and tiny powder-like particles.

All this friction and speed inevitably generate both heat and static electricity. Too much heat is bad for your brew because it cooks away the volatile aromatic and flavor compounds in your coffee, promoting a subtly drab and underwhelming cup. Static is also a nuisance because it sends grounds fluttering messily out onto your countertop and clinging to surfaces both on and inside the grinder, including inside the grounds-catching bin or container, making it harder to pour or spoon grounds out into your filter.

Grounds stuck inside a burr grinder can also lead to maintenance issues eventually, while more immediately they can foil the freshness of subsequent brews by coming unstuck and getting swept out along with fresher grounds, thereby imparting off-flavors and changing the character of your cup. Different designs of grinder typically include different strategies to mitigate both heat and static, with varying success, as described in our reviews.

After the bean’s initial explosion, as heat and static are potentially mounting, the particles that are bigger than your ideal grind size are hopefully further broken down to something close to an optimal average size for the brewing method you choose.

The Importance of Particle-Size Consistency

When you dunk something porous under water, the time it takes for water to soak all the way through it has a lot to do with its size. If it’s bigger, water takes longer to get to its center, and vice versa if it’s smaller. This is true of each individual particle of ground coffee.

Coffee releases different substances into the water at different points in time, and the best way to control that reaction — to get the stuff you want out of coffee and avoid the stuff you don’t — is to brew with coffee particles that are as close as possible to a uniform size and shape.

We know that after a fresh-roasted bean’s interstitial CO2 is nudged out upon initial contact with water (i.e. the bloom phase), the first chemical compounds drawn out of coffee are its acids, oils and more pleasant aromatics such as fruity and flowery notes. Next come the sugars, which are major players in the overall yum factor of your cup, and after that come some bitter and astringent qualities contributed by the actual cellulose stuff of the roasted seed.

An “under-extracted” brew is the result of water passing through too quickly, or perhaps at too low a temperature; it may taste peanutty, shallow or sharp. Similarly, an “over-extracted” brew will be regrettably bitter and astringent due to water mixing with coffee for too long, or at too high a temperature. To craft an ideally delicious balance of acids, fats and sugars, full of complexity and character and relatively free from bitterness, you need to keep the mix of water and grounds within the ideal temperature range (around 200 ºF), and you need to be able to separate the brew from the ground coffee at the right moment.

Better Grinder = More Control

Managing water’s ability to flow through coffee in order to time that separation successfully comes down to a matter of dose and grind. A subtle change to the ratio of water to coffee in your recipe is one way to alter the brew; another way is to grind the coffee either more coarsely or finely in order to adjust its resistance to the water, bearing in mind that these variables are especially closely linked in non-immersion methods such as drip, pourover and espresso.

“Dialing in” these variables takes a bit of trial and error. What’s always true, though, is that better grinders give you more control over your adjustments to the grind, and however it is you like your coffee, the closer the particles in your filter are to the same size, the easier it is to control the flow of water.

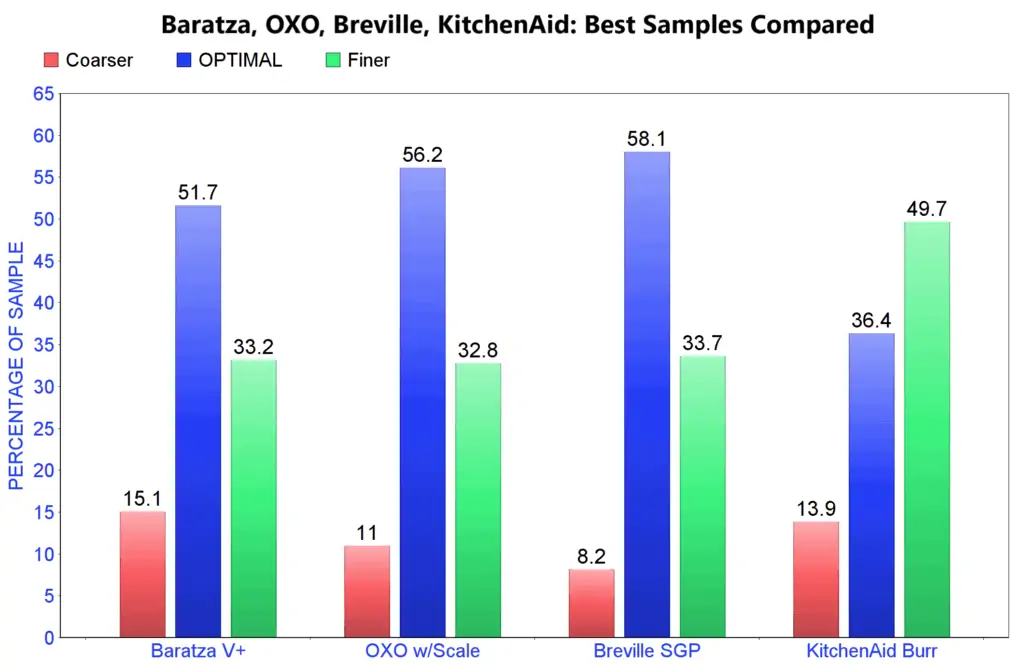

Summary grind consistency test results based on laser particle size distribution analysis by Horiba Instruments for the four grinders reviewed for this report. Six samples were tested from each grinder representing various grind settings (coarse, medium, fine) and two degrees of roast (light and medium-dark). Shown here are results for the best-performing sample among the six produced by each grinder. The blue column represents the percentage of the sample reduced to a range of particle sizes we identified as optimal; the red column the percentages produced coarser than optimal, and the green finer than optimal.

For an explanation of how we determined our optimal range of particle sizes click here.

Blades vs. Burrs

A deep and irrevocable line in the sand exists between grinders built around a spinning blade that whacks beans into wild smithereens, and grinders with one spinning and one stationary serrated burr that, by feeding beans through the space between the burrs, are far more likely to reduce whole beans into a tidy pile of more uniform grounds.

Even the worst-performing burr grinder is built with some consideration of the alignment and calibration of the burrs, which are themselves engineered with some consideration of the sharpness and geometry of their teeth. The fast-spinning blade of a blade coffee grinder meanwhile acts more like a hammer than a scalpel. There’s no accounting for how many times a chunk of bean will come into contact with a spinning blade, and every time it does, it only gets clobbered into another unpredictable spray of different-sized particles.

Horiba Help

In the course of evaluating grinders for this report, we reached out to our friends at Horiba Instruments, a Japanese manufacturer of precision instruments for measurement and analysis with offices and labs in various locations internationally. We sent samples of ground coffee to their lab in Irvine, California, for particle size analysis by laser diffraction. Our samples included grounds generated by the four burr grinders we review for this report, as well as two samples ground by blade grinder.

The popular, top-selling spinning blade grinder that we bought brand new for this test predictably produced the wildest variety of particles by far; the furthest from what anyone could call a consistent grind. While not every blade grinder is exactly alike, we find them apparently similar enough to be comfortable in issuing a blanket recommendation against their use for grinding fine coffee. They’re better than buying pre-ground, but if you can manage it, get a burr grinder.

Conical vs. Flat Burrs

The two main shapes of coffee grinder burrs are conical and flat, and the speed at which they spin is determined by the manufacturer based on their size and geometry, the torque of the motor, and other factors. The shape, size and RPM of burrs in a grinder do make a difference in the consistency of the grind, although raw specs alone don’t always tell the whole story.

Conical burrs consist of a central cone-shaped inner burr with teeth on its outer surface that spins within a stationary ring-shaped burr with teeth on the inside. Flat burrs are two discs serrated on facing sides, one spinning and one stationary. While most burr grinders built for home use employ conical burrs, there are also many that go with flat, and while there are potential advantages to each, there are also drawbacks. The average coffee drinker probably won’t notice any difference in the cup, but as manufacturers almost always specify which type they’ve built into their machines, it may help clear up some confusion to know the arguments pro and con for each shape.

Conical burrs, which are cheaper to manufacture, can also more efficiently pull beans into their teeth and process them down to size. Therefore they can produce an effectively consistent grind at lower RPMs, which in turn means the grinder can potentially operate more quietly and produce less heat. Yet the geometry of conical burrs is such that they also tend to produce a bimodal or varying size distribution of grounds.

Flat burrs, on the other hand, have a greater potential to produce a more consistent particle size. Therefore the more obsessive home or cafe baristas seeking the highest level of precision and control might gravitate towards flat burrs. But in reality, only the very best grinders on earth come anywhere close to uniformity. So in machines designed for affordability and casual home use, the difference comes down to something more theoretical than actual, with neither flat nor conical burrs staking claim to superiority by default.

Further Issues and Features

Grind consistency trumps all, but in cases where differences in that category are relatively small, as is the case with three of the grinders we review for this report, there remain other important features that impact a machine’s usefulness and the user’s experience. The smoothness and precision of the grind setting adjustment system is very important, as is the machine’s overall build quality and style. The design of the cup that catches the grounds is important, as is the noise level of the machine when it’s in action.

Most grinders offer a timer that automatically stops the grind after a user-designated period of time has elapsed, while others, including one grinder we review here, the Oxo Conical Burr Grinder With Integrated Scale, weigh the grounds to determine when to stop the process. In either case, we test these functions for their convenience and accuracy. We also take note of a grinder’s hopper capacity, how much coffee builds up on the inside of the machine in normal use (grounds retention), and whether the machine makes it convenient to load and grind just one dose at a time to accommodate those who prefer to store all their beans in air-tight containers and only expose enough for one brew or batch at the moment they make it. And finally, of course, there is the question of whether a grinder’s overall performance and features ultimately merit its price.

All too often, coffee-gear shoppers relegate the grinder to an afterthought. Yet beans have to pass through a grinder before they come anywhere near a brewer. While the way you brew your coffee is largely up to you, it’s your grinder’s job to lay the groundwork, so to speak, for success.

Read Reviews