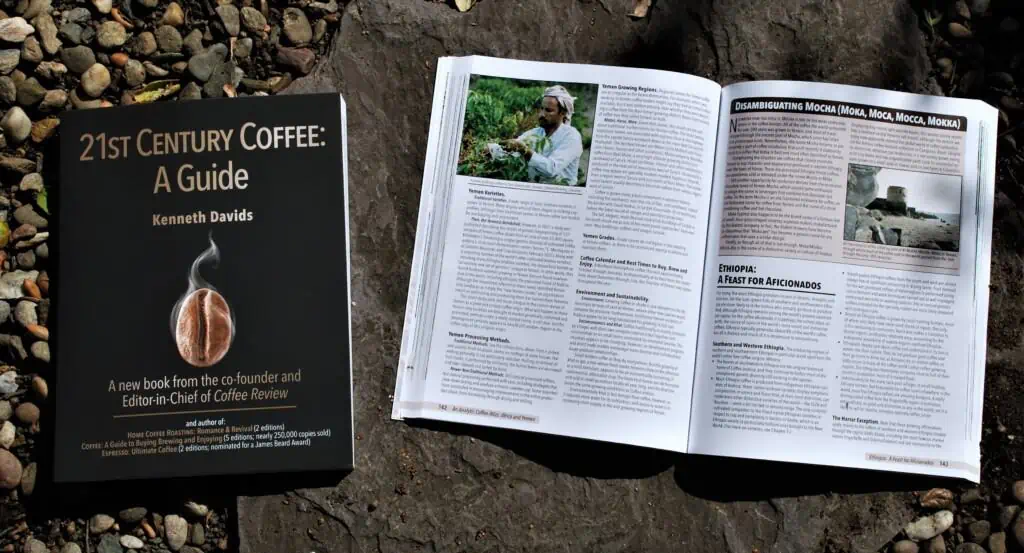

“When my first book about coffee came out in the 1970s,” Coffee Review editor Kenneth Davids says, “people I met at parties used to wonder how I managed to find enough to write about coffee to fill a whole book on the subject.” Given the explosion of coffee innovation and change since then that Davids describes with affectionate yet thorough detail in his latest book, 21st Century Coffee: A Guide, coffee insiders today may wonder how he managed to get away with writing one new book this time rather than two or three. Nevertheless, he appears to have gotten most of the latest innovation and excitement in coffee into his latest volume, enriched by a perspective afforded by his over forty years of active engagement with the specialty coffee world.

The book offers particularly detailed chapters on coffee tasting and language, recent specialty coffee history, tree varieties, the latest processing wrinkles, and well-illustrated chapters (with maps, of course) on various coffee origins. Rather than simple histories focused on geography with a few lines on tasting and coffee types, Davids offers detailed analyses of the coffees produced in these countries, including both traditional and new coffee types and assessments of social and environmental issues. He concludes with chapters on coffee roasting, lots on brewing, on big-picture environmental and social issues, on coffee and health, and an afterword on the impact and challenges of espresso brewing.

He offers provocative asides, too, on the relationship between coffee and wine, on whether the historic success of coffee as a beverage is owing to its taste or its caffeine content, and much more.

Davids lives in the San Francisco Bay Area, in the old town of Alameda, and I live in San Antonio, Texas, so this interview was conducted by Zoom and email and was edited for publication.

The book is available now, discounted, and signed for Coffee Review readers at www.kennethdavidscoffee.com. Use code 5offcofrev at check out.

Christie Slaton Zgourides (CSZ): In your book, you write about being there, literally on the spot, when the specialty coffee movement lifted off in the late 1960s in the San Francisco Bay Area. No one could have known then that a global shift in coffee and coffee culture was dawning. What was it about those early cups of coffee that captivated you?

Kenneth Davids (KD): Like a lot of young Americans of my time, I learned about the pleasures of cafés while vagabonding in Europe. When the first take on a European-style café opened near where I lived in Berkeley (the Caffè Mediterraneum), I started spending all day there, writing and talking and working. But I soon realized that there was this phenomenon, coffee, at the heart of the place and the experience, and I knew nothing about it. Turns out that very few people did. So, I tried to understand coffee by engaging with it. And when I did, I found I had stumbled on a mystery that touched on so many important issues: social, historical, economic. And they were all woven into the act of smelling and tasting, the most intimate way we understand the world. I certainly didn’t speculate about what might happen in the future. I just followed the path of curiosity and pleasure leading to knowledge.

The pioneering Caffè Mediterraneum in Berkeley around 1970, one of the places where Davids reports first being smitten by coffee. Courtesy of Diane De Pisa from her book Berkeley Then: A Photo Diary of the Sixties Scene.

CSZ: Once you discovered specialty coffees, you continued to do more than casually drink them. How did you go from reading the exotic coffee names on the shelves at Peet’s, as you mention in your book, to being a coffee expert in your own right?

KD: At the time, I was restless and impatient with my college teaching job, so I decided to open my own specialty coffee shop. It was also a coffee house, meaning espresso by day and wine, poetry and jazz at night. Not to mention light meals all day long. That was in about 1972, I think. I loved the specialty coffee part (the poetry and jazz were fine, too), but I quickly lost interest in the challenges of hiring short order cooks and maintaining portion control. So, my partner and I sold the business and I made enough money to take a year off. By then, I had come to know a lot of the people who were creating specialty coffee on the West Coast, including Alfred Peet, the pioneer importer Erna Knutsen, and innovators now largely forgotten: Jim Hardcastle of Capricorn Coffee, the Mountanos family, and many others. I also knew by then that nothing significant had been written about coffee since 1935 and the second edition of William Ukers’ All About Coffee.

I had time, I had access to a community of specialty roasters and importers, so I decided to write a book to fill that historical gap. I didn’t approach writing about coffee as a journalist might, by patching together expert interviews on top of library research. Instead, I attempted to actually learn coffee, to bring green coffee home and roast it, cup it, prepare it in a variety of ways. I did some modest coffee traveling, enough to know how tough it was to be a coffee grower, but how deeply committed most were.

CSZ: That first book — Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing & Enjoying — was a success.

KD: It definitely had a lot of influence on the development of specialty coffee. It never became a bestseller, but it kept selling. Over the course of about 30 years and five editions, it sold around 250,000 copies. With the success of the book came many more opportunities to taste coffees, to travel, to consult, to hang out over cupping tables, to learn, enjoy. I grew with the specialty industry, experiencing it existentially, in body and mind. As I learned about coffee, specialty coffee was learning about itself, and building a dynamic new coffee world atop the old one.

CSZ: You mentioned asking baristas questions about a particular coffee only to have them quote outdated material from your books. What did you think the first time a 20-something unknowingly quoted your own work to you?

KD: I felt disappointed, obviously, because I wanted to learn more about what I was tasting. But that sort of incident doesn’t happen much anymore. Today most baristas are part of a culture that has gone beyond my previous books. That’s why I wrote this latest one.

CSZ: How is this new book different from your previous books, particularly from its immediate predecessor, the fifth edition of Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing & Enjoying?

KD: Well, it has more in it, for one thing! And it has color photos, lots of them. And it has a major focus on tasting coffee, much more than in my earlier books. I introduce the latest thinking about the physiology of tasting, the pleasures and the languages of tasting, and how to connect what one tastes with what went on at the coffee farm or the roasting room.

Above all, I do my best to bring the entire story of specialty coffee up to date. The specialty world has erupted with change and innovation over the last 15 years. These changes are being created out of sheer enthusiasm, often grassroots enthusiasm, for understanding coffee, for pushing its limits. You find this enthusiasm among coffee aficionados who are using Kickstarter financing to create new refinements on brewing; among roasters who are understanding roasting better through the use of computers and disciplined tasting; among coffee growers who almost daily are coming up with new processing wrinkles; among coffee exporters who are creating crucial new links between growers and roasters; among scientists who are bringing the tools of their disciplines to understanding coffee better and trying to assure its future. And I feel that I brought that same enthusiasm to researching and writing this book.

CSZ: Yes, that enthusiasm as well as your affection for the coffee world come through clearly. I am sure that being the editor and lead cupper for Coffee Review helped with all of that.

KD: Definitely. My younger colleagues, Kim Westerman and Jason Sarley, were essential, as were the roasters who send all of the latest experiments and coffee types to us to cup!

CSZ: One more book question. Your previous books were all published by St. Martin’s Press, a well-known and well-established publisher. But this latest book is published by CoffeeReview Books, an imprint you apparently founded. What’s the story there?

KD: I had signed a contract with St. Martin’s to do a new, sixth edition of Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing & Enjoying. But I felt that given all the changes in coffee, this new edition needed to be longer than the old editions, with more elaborate graphics and four-color printing. When my editor at St. Martin’s saw the working draft, he felt a book of the size and complication I proposed would not fit in at St. Martin’s, and he generously released me from my contract. About the same time, I was offered the editorship of a proposed Oxford University Press Encyclopedia of Coffee. I signed a contract for that project as well, but for reasons related both to me and to changes at Oxford Press, the project did not move forward. So, in effect, I’ve created my own encyclopedia of coffee, in my own voice, by fleshing out and bringing my old book up to date.

CSZ: Your book covers the globe, or at least the parts of it that grow coffee. You have engaged with people, places, and climates in all these regions. What, for you, has been most rewarding about seeking out coffee at its source? What are the places you most want to return to again and again, and why?

KD: This may sound nicey-nicey, but it’s true. For a visitor, all of the coffee lands are great. The weather is almost always good, the producers engaged and hospitable, and you can always find great coffees in their respective styles. I spent a total of almost two months in Yemen, for example. An extraordinary place (at least for male coffee romantics) in which coffee was grown, processed, and consumed exactly as it had been at the dawn of coffee history. At the other extreme are the many months I’ve spent in Brazil, with its sophisticated coffee technology, vast scale, and delightful people. Guatemala is particularly important to me, as is Indonesia. Southern Ethiopia is, of course, extraordinary. Even for the humblest of Ethiopians, coffee is woven into their lives both as crop and beverage. Hawaii — well, Hawaii is Hawaii — at its heart, subliminally seductive in ways that transcend weather and overcome all but the most blatant touristic exploitation. And the best small-farm Hawaii coffees are getting better and better. Then there all the other coffee origins, all wonderful, all original: Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Kenya, India …

A couple enjoying coffee during a village coffee ceremony, Yirgacheffe region, Ethiopia, 1999. Courtesy of Kenneth Davids.

CSZ: What about the people? I notice in the acknowledgments part of your book you thank a couple of hundred people you’ve known or worked with over the years, people from all over the world.

KD: As anyone who travels for coffee knows, coffee people can be extraordinarily hospitable. In Yemen, before I met my wife, a coffee producer I was friends with became troubled that I was not a Muslim. He finally told me that if I became a Muslim, he would find me an excellent wife. I thanked him but told him that I could take care of the wife thing on my own. I had my personal criteria on the subject, and this prospective wife doubtless would have hers, plus I was not much into religion of any kind. He became thoughtful. The next day he said, Ken, if you become a Muslim, I will find you a wife who knows a lot about coffee and who has a Ph.D.

A Yemeni boy standing among the branches of a just-picked coffee tree, 1997. Despite the expansion of the specialty coffee movement in Yemen, the majority of Yemeni coffee-growing families continue to struggle. Courtesy of Kenneth Davids.

That was the only time coffee hospitality extended to marriage-brokering, but I did later meet my wife, Iara, in Rio de Janeiro while traveling to film a coffee documentary.

CSZ: So Iara has a Ph.D?

KD (laughs): She does not. She has an MA in Clinical Psychology and is a successful marriage and family therapist. It’s possible she considers me her masterwork, albeit one still in progress. In regard to coffee lands, Iara constitutes Brazil for me, in her charm, her quick, light-footed intelligence, her samba, her capacity for hard work, her joy, her love of fine coffee, not to mention her capacity to consume large amounts of it.

Coffee friends, 1998. Miriam Monteiro de Aguiar inherited Fazenda Cachoeira in Minas Gerais, Brazil, from her father. Shown here with her husband Rogério, she has operated it ever since with unrelenting commitment to progressive environmental and social ideals. Courtesy of Kenneth Davids.

CSZ: That’s a wonderful story that gives new meaning to the romance of coffee! Wine usually gets all the credit for romance. Interestingly, we’ve seen the temptation to compare coffee to wine, especially as the complexities of coffee have become more understood and appreciated. This seems to make you cringe a little. Why?

KD: In the big picture, coffee and wine have a whole lot in common. Both are richly complex and fascinating expressions of the dialogue between nature and culture, and both make us feel good when we drink them. But there also are many differences. Coffee is considerably more complex and shifty in its chemistry than wine. And coffee is far more demanding for players all along the supply chain. For example, a great cup of coffee typically requires expert contributions from at least three different parties: grower, roaster, and the person who brews it. By comparison, once it leaves the winery, wine is a bit of a fait accompli in a bottle. The socio-economic context of coffee also is far more fraught with controversy. Wine certainly has its share of exploitation, but the commercial commodity coffee industry is flat-out built on economic exploitation of the rural poor. Specialty coffee was founded in part to try to break the beverage out of that pattern of systemic exploitation.

CSZ: Your response here pivots quickly to the darker side of coffee, and your approach throughout the book is an unvarnished, unflinching honesty about the realities of coffee production, including the threat of climate change and the hope of new genetic studies/varieties. What are your greatest concerns and highest hopes for coffee over the next 10-30 years?

KD: The greatest concern is, of course, to quote the Leonardo DiCaprio character in Don’t Look Up, “We’re all going to f___ing die!” When you’re working in fine coffee you are always confronted by the relentless, unforgiving threat of global warming. Coffee breeders are working in admirable ways to try to save Arabica coffee with hardy but cup-distinctive coffee types. Nevertheless, I fear that we may die drinking lousy Robustas that can take the heat while climate change wipes out everything else, including us. (Except, perhaps, for exquisite high-elevation Arabicas consumed by the super-wealthy few who live in fortress-like estates on the upper slopes of Mauna Loa.)

Davids listening to coffee farmers in Papua New Guinea in 2005. Their coffee was excellent; they suffered due to remote water sources and difficulties getting their coffee to mills. Courtesy of Kenneth Davids.

That last crack is rather snarky, but it reflects a genuine concern. While super high-end microlot coffees are proliferating, and super low-end blended supermarket coffees hold their own, the good, dependable, clean-tasting washed Arabicas that used to dominate in the middle of the market are disappearing, just as the American middle class may be disappearing, hollowed out by economic pressures and technology-driven change.

On the other hand, the prospect of more and more highly differentiated fine coffees can be seen as hopeful, in the long run, a sign that coffee growers and their exporter partners are beginning to take expressive charge of their own future. The hope is that coffee may eventually approach wine in the range and variety of options, from auction wines that cost thousands of dollars a bottle to two-buck Chuck, with plenty of niches between.

CSZ: That takes us back to the wine/coffee parallel. Given specialty coffee’s increasing complexity and rapidly growing market, do you see room for coffee complementing food? In other words, do you think we should be talking about coffee and food pairings? Are there coffees that you prefer with different foods or coffees that you prefer at different seasons?

KD: Coffee is a less stable and less predictable product than wine, so laying out rules or even suggestions for food matching is more difficult with coffee than with wine. Also, once past breakfast, attitudes toward combining coffee with food vary by culture and individual. Some prefer to take their coffee after large meals, not during. Rather than drip coffee with a main course, they prefer espresso with dessert, for example.

Personally, I enjoy consuming drip coffee with a midday meal. I generally prefer clean but mildly fruit-forward styles of natural coffees with breakfast, and the equally pure, but more sweet-savory style of washed coffees with food later in the day. Fine Kenyas, for example, can be extraordinary with an afternoon meal.

CSZ: In your book, you discuss almost every possible means of brewing coffee in considerable detail. How do you brew coffee at home?

KD: In the morning, I make coffee for Iara and myself with a Technivorm Moccamaster with a thermal carafe. The Technivorm was the first automatic drip machine certified by the Specialty Coffee Association, and I still find it’s one of the best, if priciest. We drink a lot of coffee in the early part of the day, and we both like to start work well provided for. In the afternoon, I may make a single cup for myself using the Aeropress and my own idiosyncratic recipe, which I had the temerity to put in my book. Or a Hario V60, using a pretty standard recipe and pour.

CSZ: Finally, just for fun — if you were stuck in a remote mountain cabin for a month and you could only take three coffees with you, what would you choose?

KD: I might be so desperate near the end of that time that anything I brewed would taste good! But I would take along the last three coffees we rated 94 or better at Coffee Review.

CSZ: With that selection, I think you would have a lot of people wanting to join you! Thank you, Ken, for your coffee insights that explore the challenges and the hopes for a great cup. We encourage everyone, regardless of experience, to learn more for themselves in your new book, 21st Century Coffee: A Guide.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: CHRISTIE SLATON ZGOURIDES

Christie Slaton Zgourides is a freelance writer with an eclectic background as a business manager as well as a professor of composition, critical thinking, and literature. Most importantly, she is a passionate coffee drinker.