Coffee is spread out on a concrete patio to dry in Chiapas, Mexico. Photo by Kim Westerman.

While Mexico is somewhat under the radar when compared to more popular coffee origins, the country has been producing coffee since the late 18th century, and given recent developments, may well be poised to become a model for coffee production in the 21st century. In this month’s report, we review nine exceptional coffees from four different Mexican growing regions.

Coffee farmers everywhere face various barriers to success — some more than others — including climate change, pests and plant diseases, and prices for their annual crop too low to survive on. But narratives of resilience also abound, and if our findings in this report are any indication, Mexico may be a prime example of both increased quality and improved infrastructure achieved in the face of adversity, developments boding well for the future.

A Brief History of Mexican Coffee Production

Coffee is grown in 15 of Mexico’s 31 states, but the vast majority is grown in the south, in Chiapas (approximately 41 percent), which borders Guatemala and has excellent conditions for coffee production (higher growing elevations and a cooling marine influence from both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans). The other main regions of production, in order of output, are Veracruz, Puebla and Oaxaca. Though coffee is only 141st on the list of products most exported by Mexico, it was the 10th largest exporter of coffee in the world in 2020, with the lion’s share of green coffee produced going to the United States (49.7% of total production).

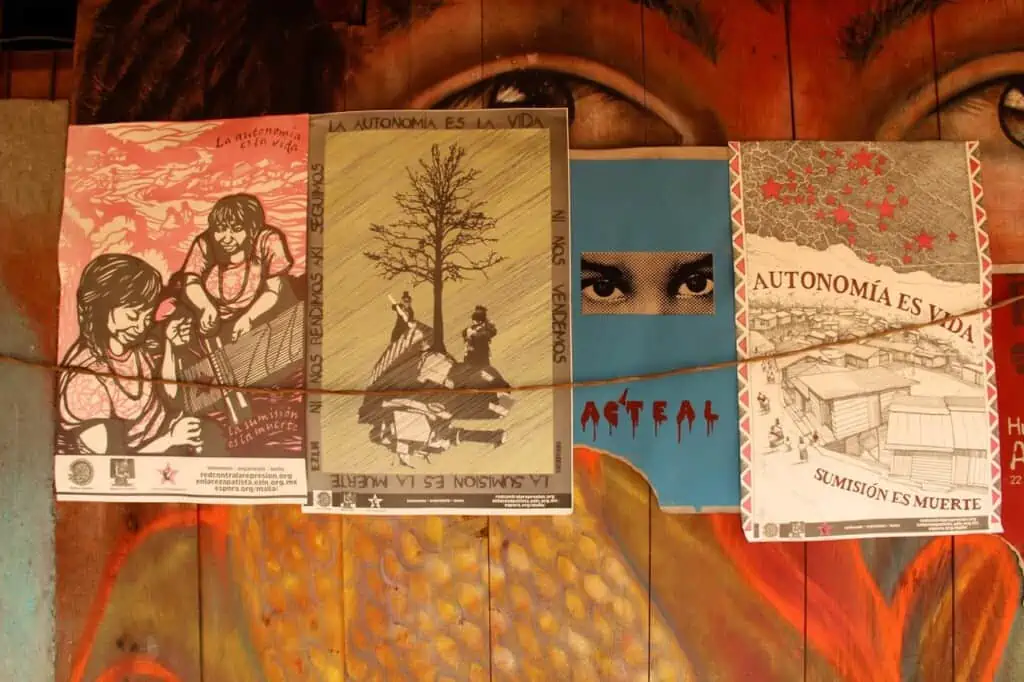

The majority of coffee grown in Mexico is processed and sold via cooperatives, of which there are currently more than 600 throughout the country. This model is not unique, by any means, but it took hold in Mexico as a way for indigenous groups to maintain cultural identity and autonomy, and as a grassroots response to the lack of governmental intervention when crises arose. The Zapatista movement in Chiapas, in particular, maintains strong values around organic and other traditional coffee-farming practices, which is one of several factors that distinguish and differentiate Mexican coffee production from many other growing regions in Central and South America. And while there are certainly private coffee estates in Mexico, it’s notable that eight of the nine of the coffees we review this month are either from cooperatives (official or unofficial) or individually owned farms that have partnered with neighboring farmers in a collaborative way; only one is from a single farm. Though the Mexican government is more involved in the coffee industry, of late, than in earlier decades (more on that below), it seems fair to say that the coffee industry’s strong communal impulses have remained the bedrock of the country’s success.

Sustainability Certifications in Mexico

There are several options for producers in Mexico seeking third-party certifications for their coffees, along with the price premiums associated with these certifications. All certifications to some degree address ecological, social and economic issues in their standards, but emphasis differs by certification. Organic certification is most popular with Mexican producers. In most years Mexico is the second-highest producer of organic coffee in the world, just behind Peru. Three of the coffees we review this month are organic-certified. Fair Trade, with its particular emphasis on cooperative arrangements among small-holding producers, is also very important in Mexico; among the nine coffees reviewed this month, two are certified Fair Trade. Rainforest Alliance certification (now merged with Utz Certification under the Rainforest name) is historically structured to appeal to larger farms seeking data-driven, holistic validation of their sustainable practices, although its new standards include specific consideration of smallholders.

Talking with smallholding farmers in Chiapas about their work with Fair Trade USA. Photo by Kim Westerman.

None of these certifications is without controversy — about the standards themselves and in terms of what is ultimately best for people, the environment, and the coffee industry — but for the purposes of this report, suffice it to say that there are competing systems at play, complicated by the increasing influence of “direct trade,” a set of voluntary practices that can be very appealing for both farmers and green buyers. And there are additional steps roasters must take, with each certification, to be allowed to claim the certification on their roasted coffee, involving fees and documented practices that are not always completed. For example, a roaster may have purchased a coffee certified organic at origin but be unable to legally display that certification on the roasted coffee because the roastery is not also certified organic.

Government Involvement and Support

In 1973, the Mexican government established a national coffee organization, INMECAFE (Instituto Mexicano del Café) to provide financial and technical support to farmers, but it dissolved in 1989 with the termination of the export quota system maintained by the International Coffee Agreement, leaving coffee farmers to fend for themselves, as well as find their own sales channels. AMECAFE (Asociación Mexicana De La Cadena Productiva Del Café) is currently the most prominent coffee association, and it’s having some success in regaining the government’s attention in recent years.

Since 2015, Mexico coffee farmers have been hit hard by roya, or leaf rust, a devastating fungus that attacks the leaves of coffee plants, spreads easily and is very difficult to treat. This crisis has spurred SADER (Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development) to partner with AMECAFE, along with

the National Service of Health, Food Safety, and Food Quality (SENASICA), the Integrated Coffee Production Chain (Sistema Producto Café), and some private-sector companies to help by establishing plant nurseries, grafting and cloning, and providing training through the government-sponsored Sustainability and Welfare for Small Coffee Producers (SUBICAFE) program. A 2019 report by the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service suggests that Mexico is continuing to rebound well from the leaf rust crisis.

Top-Scoring Coffees

As with all Coffee Review reports, our view of what is happening now in Mexico is limited by the submissions roasters send us, as well as what is available in the market during our cupping window. Because the coffee supply chain is very complex, green coffee arrivals in the U.S. purchased by importers and roasters are impossible to precisely time, so we usually miss some potentially excellent coffees for our reports. In this case, according to Vernaé Graham of Fair Trade USA, many of the Fair Trade-certified coffees from Chiapas have not yet arrived, though we did get our hands on a few.

Luckily, we still received a wide range of origins, certifications and processing methods among the 30 coffees we received for consideration. The top-scoring nine, which we review here, encompass four regions (Chiapas, Guerrero, Nayarit and Oaxaca) and four processing methods (washed, natural, honey and anaerobic).

Processing Innovations As Value-Added

As in many coffee-producing countries, Mexican farmers are starting to work with processing methods that fall outside the traditional washed method that has, for decades, defined export-grade coffees from Mexico. These alternative methods generate the kinds of cup profiles that are currently trendy in the ultra-specialty coffee world, and when successful, earn their producers higher-than-average prices.

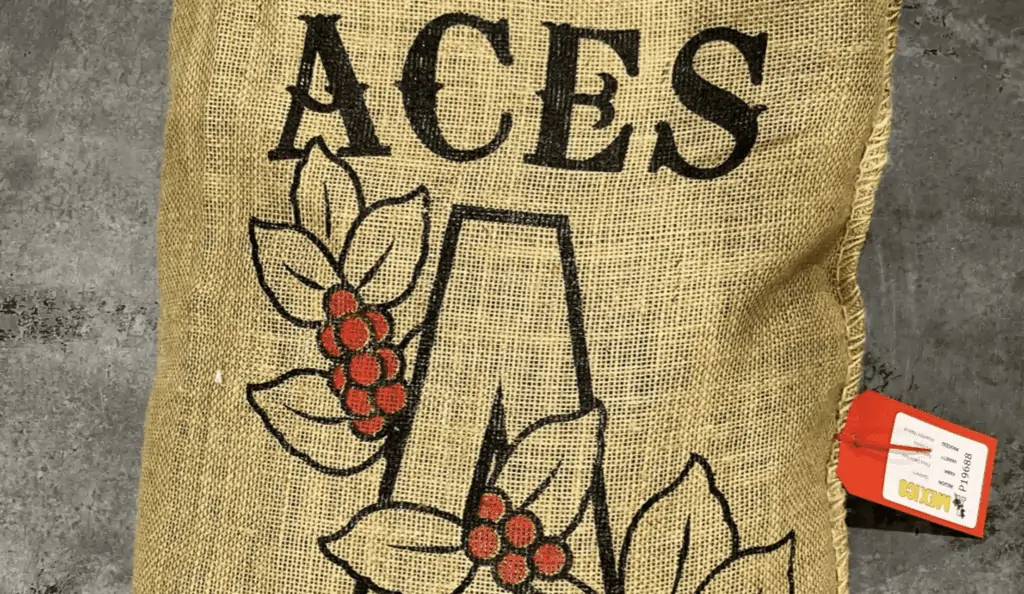

The highest-scoring coffee overall, at 94, is Revel’s Finca Cerro Azul Aces Lot — processed anaerobically (fermented in the whole fruit in a hermetically sealed vessel) and produced by a single farm. It is richly aromatic and fruit-toned with ballast from deep chocolate and sweet floral notes, and an intentional sweet ferment. This is a style of cup we now see on a weekly basis from regions throughout the coffee world, as anaerobic processing variations proliferate, bringing their particular tendencies to the sensory potential of the bean. (Read more about that here.) And it’s clear evidence, along with the four other anaerobic-processed samples we received, that Mexico is climbing on the processing-experimentation bandwagon. Fourteen of the 30 submissions were natural or honey-processed, which leaves only 16 traditional washed coffees in the mix. This is not surprising given the global trends we’re seeing, but it is a rather rapid departure from the preponderance of washed Mexican coffees we’ve reviewed in the recent past.

Revel Coffee’s submission for the Mexico tasting report was a Finca Cerro Azul Aces Lot, produced in the Guererro State. Photo courtesy of Revel Coffee.

Revel’s Gary Theisen says, “I think this might only be about the fifth coffee in 15 years that I’ve brought in from Mexico. Most of the importers I have a relationship with tend to list coffees from Mexico that are more intended to serve as a base component for blends. Single-estate coffees that can stand on their own have historically proven to be a bit of a challenge to find. In the case of the Cerro Azul, it had so much quality and intrigue to the cup that I couldn’t pass it up as a quality exemplar from the region that I hope is a harbinger of ubiquitous standout Mexican offerings to come.”

We rated five coffees at 93, one a natural-processed coffee and one a honey. Fumi Coffee Company’s Chiapas Las Margaritas Pache Natural was produced under the direction of Byeong Soo Kim (AKA Teddy) of Finca Don Rafa, whose model is to work with neighboring farmers to help all improve and prosper together. Fumi’s roasted version of this coffee is rife with tropical fruit notes and sweetly herbaceous.

The one honey-processed coffee we review, roasted by Badbeard’s Microroastery in Portland, is a Chiapas Chimhucum “Semi-Washed.”Badbeard’s Justin Kagan has long seen Mexico as an under-appreciated origin. He was principal cellist of the Mexico Symphony from 1990-1998, back when it was difficult to get good coffee to drink as a resident of the country because, as he says, “The good stuff was all exported.” But he lived there long enough to find the good local coffee and roast it with friends, so he has always known the quality was there. Badbeard’s Chiapas, produced by an unofficial collective of smallholding farmers, is delicately sweet and subtly complex, with dried stone fruit, cocoa and citrus notes.

Community announcements posted on a mural commemorating the 1997 massacre in Acteal, Chiapas. Photo courtesy of Amavida Coffee.

Mostra Coffee’s Nyarita Canela (92) feels like a real discovery, given how few coffees we’ve seen from the Nayarit region in the past. Natural-processed, it’s crisply sweet and fruit-driven with notes of dried plum, hazelnut, cocoa powder and marjoram. Ryan Sullivan says, “We chose this coffee not only because we feel like it is an excellent coffee, but also to help support the community that it comes from. This has been an ongoing relationship for Mostra working with the TAMBOR Cooperative through San Cristobal. In 2012, coffee producers in the town of Huaynamota were in financial turmoil. Betrayed by a trusted colleague, the organization was left with crippling debt that was passed on to community members who had personally cosigned the loan. CAFESUMEX and San Cristobal worked with TAMBOR to negotiate their debt terms and begin the road to financial recovery. Seven years later, TAMBOR has financially recovered. Since 2015, TAMBOR has exported its crops debt free.” TAMBOR is one of many examples of the success of the cooperative model in Mexico.

Turning coffee to ensure even drying at Cafe Capitan in Chiapas, Mexico. Photo courtesy of Red Fox Coffee Merchants.

Classic Washed Coffees Remain Solid

Despite their numerical minority in terms of the total coffees we received for this report, four of the nine coffees we review this month are in the traditional washed style. All offer versions of the classic Mexico cup profile we readily recognize — and all are produced by cooperative groups the country is known for.

Amavida Coffee Roaster’s Maya Vinic (93), from the cooperative of the same name, displays notes of baking chocolate, almond butter, date, clove and magnolia, and is certified both organic and Fair Trade. Speckled Ax’s Capitan Maragoype (93) has savory underpinnings with notes of hop flowers, cinnamon and fresh-cut cedar supporting top notes of black cherry and dark chocolate. Amavida’s Jennifer Pawlik says, “Mexico coffee and the farming families are deeply rooted in our own origin story. Amavida has sourced coffee from Maya Vinic since our early days and has also supported coffee producing communities in the region through project work with On the Ground Global (OTG). In the past there was a lot of focus on access to clean water, which has now expanded to agronomy projects and collaborations with OTG and Cooperative Coffees (through their Impact Fund). We also work with an all-women’s cooperative in Chiapas, Mexico which in turn gives further support to project work with OTG in the region.”

Wonderstate Coffee’s Ozolotepec (93), also certified organic, is perhaps the most classic of the coffees we cupped — sweet, balanced, chocolaty and nut-toned — and was produced by members of the members of the UNECAFE Cooperative. Caleb Nicholes says, “We love Mexico as a coffee origin because of the older, traditional varieties such as Typica, Bourbon and Caturra grown in such wildly unique micro-climates. We love this Oaxaca Ozolotepec, in particular, as the region is so stunningly beautiful and the indigenous farmers there have such a rich and distinct cultural heritage. Producers from the UNECAFE cooperative tend to have quite small, organic farms, crafting some of the brightest and cleanest profiles in the entire state of Oaxaca.”

Pulping coffee directly into a fermentation tank at Cafe Capitan in Chiapas. Photo courtesy of Red Fox Coffee Merchants.

Camerin Roberts sent Lone Coffee’s La Cañada Oaxaca Organic (91), which we appreciated for its friendly accessibility, sweet nuttiness and gentle fruit and floral underpinnings. It was produced by members of the Union de Productores Las Flores. Roberts chose this coffee “because it has been part of the blend for our bar espresso for a while now, which is the base of our many popular espresso drinks. As a standalone, it’s fruity and not too acidic. It has a certain friendly complexity that our customers enjoy.”

And we also enjoyed the Fair Trade-certified, organic (FTO) coffee from Water Street Coffee (91) in Kalamazoo, Michigan, sourced from family-owned farms organized around the Grupo de Asesores de Producción Orgánica y Sustentables (GRAPOS), a farmers’ group operating in the municipalities of Unión Juárez, Cacahoatan, and Tapachula in the state of Chiapas. It’s a quietly complex cup with crisp apple and sweet herb notes with consistent undertones of almond brittle. Aaron Clay spoke of Water Street’s positive relationship with the Fair Trade USA organization: “The systems and support they offer make it easy to be a part of the Fair Trade movement — holding organizations to high standards by providing safe working conditions, sustainable livelihoods, and protecting the environment.”

Takeaways

Our foray into the Mexico coffee landscape, while just a slice of what’s happening on the ground, was quite heartening. Quality is high, processing experiments are widespread and successful, and the cooperative model that Mexico coffee production was founded on is holding strong. We hope the country continues to rebound from the leaf rust crisis, and we’re excited to see what becomes of the many new partnerships being formed — may they all succeed in helping farmers achieve stability and thrive.