The very day we spoke with several roasters in New England whose coffees are featured in this month’s tasting report, Dunkin’ Brands, parent company of Dunkin’ Donuts (now rebranding simply as Dunkin’) and headquartered in Massachusetts, announced plans for expansion. And the company’s “Blueprint for Growth” centers not on doughnuts, but coffee, including the relaunch of the Dunkin’ espresso beverage line. So, perhaps it’s not surprising that five of the eight roasters we interviewed mentioned Dunkin’ as one regional tradition they’re contending with.

Of course, we at Coffee Review are agnostic about brands. We cup all coffees that come into our lab blind, without regard to roaster, label art, coffee variety, origin or roast profile. Our realm is the sensory; we approach each coffee in terms of its individual presentation, evaluating aroma, structure and acidity, body, flavor and aftertaste. Only after we’ve settled on a numerical score do we reveal the coffee’s details and learn more about the story behind it. And for the record, we’ve blind-cupped and reviewed Dunkin’ coffees six times since 2002. We also cupped the flagship Dunkin’ Original Blend again for this report but decided not to publish a formal review, given that the sample we tested was pre-ground and purchased from a supermarket, rather than sourced whole-bean from a Dunkin’ location. But, for the record, we rated this rather tired sample at 82, which positions it in about the middle of the range for the Original Blend, which over the years has generated ratings between a low of 79 and a high of 87, with an average of around 84.

Transcending the Dunkin’ Influence

Although Dunkin’, now the world’s eighth-largest fast-food chain, has diversified its coffee offerings to include a dark roast and espresso, its flagship Original Blend is light-to-medium roasted. So, for many years, Dunkin’ constituted an anti-Starbucks in roast style, offering a traditional American medium-roasted cup that proposed a brighter, sweeter alternative to the big, pungently dark-roasted cup pioneered by Peet’s Coffee in the late 1960s and later adopted by Starbucks as the coffee cornerstone of a global empire. On the other hand, it also contrasted with the flat, neutral Robusta-saturated blends that dominated diner and fast-food coffee until the last 10 years or so. Plus, Dunkin’ was always relatively inexpensive and unpretentious in its presentation, making it a middle-of-the-road, medium-roasted, plain-cuppa-Joe alternative to both up-market and down-market alternatives.

Dunkin’ was founded in Quincy, Massachusetts (1950), and New England has always been Dunkin’ Donuts’ heartland. According to Donald Schoenholt, a pioneer of specialty coffee and the first president of the Specialty Coffee Association, the term “New England roast” was historically synonymous with light-roasted coffee, though “coffee chains have shaken out the diversity that once was the topography of the coffee landscape.”

Dunkin’ Donuts Original Blend coffee. iStock.

But if the smaller roasters who submitted coffees for this report — from New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Maine — have collectively reinforced a New England tradition of lighter roasting, they certainly defy comparison with Dunkin’ in every other respect.

Dunkin’ offers mainly blends, some of them artificially flavored, many offered pre-ground when sold in stores. By comparison, the coffees submitted by this month’s New England roasters were all single-origin coffees rather than blends, usually very specifically and transparently sourced. Whether purchased directly from farmers, at auction, or through an exporter, we know where each coffee was grown and processed. Furthermore, each is roasted to order and roast-dated on the label, so the end consumer is assured freshness. These practices all reflect the values of “third wave” coffee in the 21st century, which elevates specialty coffee to the level of a true artisan beverage, created in collaboration between producer and roaster.

The Nine Top-Scoring Coffees

While overall scores for our cupping of New England-roasted coffees ranged from 82-95, nine scored 92 or higher, an impressive showing. We received 43 coffees from roasters across six states. They included five Colombias, two from Honduras, one El Salvador, one Papua New Guinea, one Bolivia, and a whopping 33 from Africa origins, including one Kenya, one Tanzania, and 31 Ethiopias.

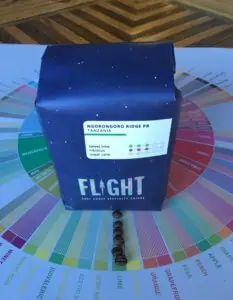

A Tanzania at the Top

Consistent with our impressions of Tanzania coffees from the northern Arusha region that have come our way over the last couple of years, New Hampshire-based Flight Coffee’s Tanzania Ngorongoro Ridge Peaberry (95) knocked our socks off with its high-toned, savory-sweet presentation and bright acidity. Owner and roaster Claudia Barrett says she loves the aesthetically pleasing roundness of peaberries, and she fell in love with this coffee on the cupping table: “It really pops — it’s deep, it’s resonant, and there is a sweet and savory structure with absolute intoxicating citrusy acidity.” She adds that “New England customers come from a broad spectrum. We have some customers who ‘get’ third wave — we don’t need to convince them. We also have customers who come to us to try to understand what the big deal is with third wave. We offer free weekly public cuppings in our roasting lab, just so customers have the chance to come in and try something new in a friendly and non-threatening environment.”

Flight Coffee’s Tanzania Ngorongoro Ride Peaberry, the highest-scoring coffee in this month’s tasting report. Courtesy of Flight Coffee.

Connecticut and Vermont Standouts

Two coffees we review at 94 have quite different backstories in terms of coffee processing and roast style. Both Willoughby’s Coffee & Tea in Branford, Connecticut and Vermont Artisan Coffee & Tea in Waterbury Center, Vermont are long-established roasters, founded in 1985 and 1991, respectively. Willoughby’s natural-processed Ethiopia Hambela is fruit-forward, with notes of mulberry and sandalwood, medium-roasted to foreground the sweet fruit. (Read 51 reviews of Willoughby’s coffees here.) Vermont Artisan’s Kenya, by contrast, is carefully roast-influenced to develop the deep floral and chocolate tendencies of the cup.

A bag of Kenya Kigutha green coffee arrives at Vermont Artisan Roasters. Courtesy of Vermont Artisan Roasters.

Willoughby’s owner Barry Levine describes his company’s place in the history of New England specialty coffee in this way: “We were part of the origination and tapestry of coffee roasting in New England, as we were one of the early specialty coffee roasters in the region (and in the U.S.). We must acknowledge George Howell as someone earlier than us by some years with his superb Coffee Connection in Boston. We were self-taught, as there were few models.”

A Probat roaster at Willoughby’s Coffee & Tea in Branford, Connecticut. Courtesy of Willoughby’s Coffee & Tea.

Howell is a coffee luminary who moved to Boston from Berkeley, California in 1974. In Berkeley, he had been impressed by recently founded Peet’s Coffee’s emphasis on single-origin coffees and fresh roasting, but not by its then-innovative dark-roasting style. After a deep dive into all aspects of coffee, he opened The Coffee Connection in Cambridge’s Harvard Square in 1975, which could be described as a medium-roasting version of Peet’s Coffee, with even more emphasis on single-origin offerings. He sold Coffee Connection to Starbucks in 1994, but a decade later went on to launch what, in retrospect, may have been the world’s first third-wave roasting company — Terroir Coffee, the first in the U.S. to offer only single-origin coffees and only light-to-medium roasts. The Terroir brand morphed into a specialized subset of George Howell Coffee from single farms and cooperatives, while the Howell website offers a more comprehensive range of single-origin options. We were unable to obtain samples of Howell’s coffees in time to properly review them for this report, but we did manage to informally try four Howell offerings and can report with confidence that the original Terroir mission of light-to-medium roasting of pure, precisely sourced coffees of great distinction continues. Howell remains a pivotal figure in the coffee landscape of New England, and far beyond. See his current blog, which offers unconventional and creative advice to novices and experts alike.

Three Solid Washed-Process Ethiopias

Of the many Ethiopia coffees we received for this report, three examples stood out at 93 for their classic Ethiopia wet-processed profiles: sweetly tart, redolent with stone fruit and deep florals, all expressive and graceful.

About Barrington Coffee’s 93-rated Feku Double, co-owner Barth Anderson says, “This coffee won our hearts with its powerful concentration of citrus and berry flavors and an elegant memory reminiscent of violet pastilles.” He agrees that the history of coffee in New England celebrates a light-roast tradition, which Barrington remains committed to today. And he says, “I like to think that our customers like what we like. Our common likes are what bind us. We may not get to know each of our customers on a deep, personal level, but together we appreciate and explore a shared sense of taste.” Coffee Review has blind-cupped and evaluated 63 Barrington coffees since 2003, so this month’s success was no surprise.

In the roastery at Barrington Coffee Roasting Company in Lee, Massachusetts. Courtesy of BCRC.

Roaster Ryder Naymik, of Boston’s Gracenote Coffee, says the Ethiopia Tadese Yonka (93) he submitted “is particularly dazzling. We’re grateful to be able to buy such a green coffee and to start with so much potential. The way it suggests a plethora of delicious teas, tart red fruit, citrus, and then leaves hints of grape, apple, and brown sugar — while not compromising on the enjoyability of its basic coffee-ness — is a success for us.”

Gracenote Coffee’s Ethiopia Tadese Yonka Gemeda, featured in this month’s tasting report. Courtesy of Gracenote Coffee.

Founded in 2012 by Will and Kathleen Pratt, Tandem Coffee in Portland, Maine has a growing following of locals who come to Tandem to experience a variety of coffees, all with an emphasis on balance and sweetness, including their 93-rated Nano Challa Ethiopia. When asked about the New England coffee aesthetic, Will Pratt cuts to the chase, saying, “We are in the land of Dunkin’ Donuts! I don’t actually think that that defines the New England coffee aesthetic, though. I think most folks just like to go to their local place where they know everybody. Third wave seems to be generally well received around here, I’d say.” The Pratts try to keep it simple: “We are looking for super-sweet, fun coffees that are easy for our customers to work with. We travel with importer friends to almost every origin we buy from every year. When we find a great coffee from a good person or group, we will do our best to continue that relationship, year after year, in order to get closer to the people who make it all possible.”

Roaster Jill Stanley behind the scenes at Tandem Coffee. Courtesy of Tandem Coffee.

More Ethiopias and a Colombia

Five of our top nine coffees are from the state of Massachusetts, and rounding out the list are a Sidama Ethiopia Natural from Broadsheet Coffee in Cambridge, a washed Ethiopia from Speedwell Coffee just south in Plymouth, and a lone exemplary Colombia from Little Wolf Coffee in Ipswich.

Derek Anderson, owner of Speedwell Coffee, says there’s good news and bad news about being “ground zero” for Dunkin’ Donuts: “The good news is that we have a high percentage of coffee drinkers, the bad news is that the coffee culture was built around cream and sugar. When folks drink our coffee, or other specialty coffee done right, it’s like a whole new experience. In metro areas of New England (Boston, Portland, Providence), third wave coffee is well established and entrenched, and it’s gradually spreading out into more suburban areas. I’d say we are at the point where most towns seem to have at least one café trying to focus on quality coffee. The lighter-roasted coffees are well received when done right, but there is definitely still a large demand in the region for the more roasty coffee that hits second crack. We do a handful of these roasts, and call them our ‘classic’ coffee profile.”

Coffee roasting at Speedwell Coffee Roasters in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Courtesy of Speedwell Coffee.

Aaron MacDougall, of Broadsheet in Cambridge, says, “The coffee culture in the Boston area has started to evolve over the last several years, from student- and tourist-driven, to one in which coffee quality, service, and the overall experience are emphasized. An increasing number of customers come to us specifically seeking higher-quality coffee experiences. On the flip side, at least here in the Boston area with its pricey real estate, the growth of an independent third (or fourth!) wave café and micro-roastery scene has been slower than in many other parts of the country. Instead, we are seeing more of the moneyed large specialty chains (Blue Bottle, Intelligentsia, La Colombe, etc.) plant their flags here.”

Broadsheet Coffee Roasters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Courtesy of Broadsheet Coffee.

Little Wolf’s co-owner Chris Gatti says of his La Cabana Colombia, “This coffee has been an absolute showstopper for us from the first time we had the opportunity to taste the green last year. It’s from a brand new project in Santa Maria, where farmers are being bolstered by investment, and this is the first year this farm has had the chance to sell its coffee as specialty. We could not be more excited about what the future holds here.”

Little Wolf’s La Cabana Colombia, featured in this month’s tasting report. Courtesy of Little Wolf Coffee.

As the specialty coffee scene in the New England region evolves, Willoughby’s Levine offers a model for success. He says, “Great coffee is for everyone. Don’t be snooty. Follow the quality, roast to your best ability, maintain freshness and price fairly.” Good advice, in New England and everywhere else.