Diedrich IR-7 coffee roaster at Old Soul Co in 2006, used to roast the original Whiskey Dreams Moka Java Blend. Courtesy of Andri Tambunan.

The idea of the coffee blend is a long and winding road. Blends give roasters an opportunity to create a coffee that evokes specific sensory properties, and blends are often designed to give consumers a consistent experience over time (much like a Champagne house approaches the non-vintage brut). But before consumers began insisting upon knowing the origins of what’s in their cup, it wasn’t all that common for roasters to label blend components on the bag, or even necessarily indicate that a coffee is a blend.

In this month’s report, we consider the “house blend,” a full 25 years after Kenneth Davids, co-founder of Coffee Review, wrote this publication’s first-ever report, which happened to be on this very topic. Embedded in that first report is a brief history of Coffee Review’s origin story, including an argument for rating coffees on a 100-point scale and a decoding of the five sensory categories we still use as a basis for our ratings.

What Is Different, And What Has Stayed the Same?

The fact that we no longer pick up the phone to order coffee by mail notwithstanding, one major change is in the vast number of coffees available to consumers. Ken reviewed 12 coffees for this report in 1997, and they were all from large roasters like Starbucks, Peet’s, Green Mountain and Gevalia (with the exception of Mendocino, California’s Thanksgiving Coffee, which was smallish, at the time). In 2022, there are countless roasters in cities across the U.S., large and small, almost all of which have at least one house blend. Add to that our reviews of coffees from international roasters, particularly Taiwan, and the number of possibilities is staggering.

What remains the same is our approach to blind cupping. We still cup coffees without knowing their identities, and we still use our five-category 100-point scale to evaluate both traditional and innovative/experimental coffee types.

House Blends as Creative License

In 2022, the story of coffee and its complex supply chain is front and center, as it should be for those of us who love it, and blends often receive as much consideration as special single-origin coffees. They give roasters a chance to craft new stories based not only around origins and processing methods but also around roasters’ own narratives of time and place. In the best examples, blending has become a downright Proustian affair.

The “house blend” has historically connoted value, familiarity and consistency. But times are changing, and we now see other approaches, too, including the “omni” or “all-purpose” blend that works as well in espresso and cold-brew format as it does in batch-brew and pourover, and special seasonal blends that change with each new crop and are not designed to remain consistent over time. And even more traditional blends are typically presented with greater detail: why these green coffee components, why these processing methods, how these coffees play well together — and perhaps more importantly, what ideas and feelings a specific blend is designed to evoke, often expressed in conceptual names. (It seems that the old “breakfast blend” isn’t as enticing as it once was.)

In the 1997 House Blends report, the 12 coffees reviewed scored between 68 and 90. Only one sample revealed the origins of the coffees inside the bag, and the disclosure was very general: “Indonesia, Central and South America.” These blends were most dramatically differentiated by roast level, which ranged from quite light to very dark.

But of the nearly 80 samples we cupped for this report, about 90% are “special” in some way, even if designed to be affordable and familiar. All reveal the blend components, either on the bag or on the roaster’s website, or both. The 10 blends we review here scored between 92 and 94 and represent a range of sensory possibility, from the nostalgic to the novel.

Classic, Familiar Blends

Even though most of the coffees we see coming from Taiwan roasters are light-roasted microlots, Kakalove Café is going for a darker-roasted homage to Mayan culture with its Obsidian Mirror Blend (93), which owner Caesar Tu says is named for the stone that was important to Mayans for both practical and ritual purposes, while also implying that one should drink this coffee black. A blend of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras coffees, it is deep and rich, with chocolate notes suggesting fudge, and a whisper of comfortingly familiar roastiness.

Charlotte Coffee Company’s 704 Blend (93), named for the North Carolina city’s area code, is a blend of two pedigreed washed coffees, Tsekaka Papua New Guinea and Guatemala Finca San Gerardo, which result in a super-sweet, caramelly cup with floral underpinnings and a rich nuttiness.

Bag of Mo’ Better Brews’ Bleek & Indigo Blend. Courtesy of Mo’ Better Brews.

Houston’s Three Keys Coffee just released the Mo’ Better Brews Bleek & Indigo Blend (92), designed for a local vegan breakfast, coffee and vinyl shop. Comprised of a washed Colombia and a natural-processed Ethiopia, it’s both deeply chocolaty and tartly fruit-toned. Co-owner Kenzel Fallen says the name is a nod to Spike Lee’s 1990 film Mo’ Better Blues about a jazz trumpeter, an association that resonates well with both the shop and its vinyl theme and Three Keys’ own music referencing, which appears in all of the brand’s coffees.

Adam Monaghan, Succulent Coffee Roasters’ co-founder, says its New Wave Blend (93) is designed not only to be drunk every day, but all day. Designed as a batch brew to fuel both work and play, it’s a fruit-forward counterpoint to washed Central America-heavy blends, more of a new-classic approach, if you will. A washed Colombia (imported by Royal) provides the chocolaty base, while a natural Ethiopia (imported by Catalyst) gives it foreground and lift.

Omni Blends

A trend we noticed most prominently in this report cupping is the emergence of the “omni” or “all-purpose” blend. Maybe the pandemic has made us all want to simplify our lives, or maybe the trend toward lighter-roasted espresso is finally intersecting with the trend toward slightly darker drip preferences, landing in a medium-roast wheelhouse that works quite well across a range of formats.

Bag of Memory Lane Blend by Nostalgia Coffee Roasters, shown with a 92-point Coffee Review medallion from 2021. Courtesy of Nostalgia Coffee Roasters.

San Diego-based Nostalgia Coffee’s Memory Lane Blend (93) might have fallen into the classic category if not for its wide range of applications. Nostalgia founder Taylor Fields, who launched the brand as a mobile shop as the pandemic began to take hold, says she needed her first coffee release to do a whole lot: “We wanted a true house blend that would do it all and, more importantly, be a porch pounder and enjoyed by all types of coffee drinkers from newbies to connoisseurs.” A Brazil natural contributes body, a Guatemala, nutty sweetness, and a Sumatra, earthy depth.

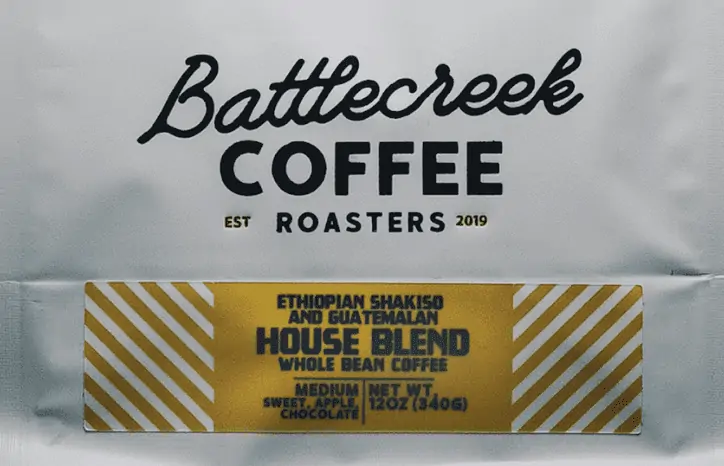

Label of Battlecreek Coffee Roasters’ House Blend. Courtesy of Battlecreek Coffee Roasters.

Battlecreek Coffee’s House Blend (92) carries a straightforward name to indicate that it’s a staple, but just above that name, the two carefully selected single-origin coffees that comprise it are listed: a natural Ethiopia Shakiso and a washed Guatemala Huehuetenango, both of which Battlecreek sells as standalone coffees. Director of Coffee Josh de Jong says this coffee was created for a partner coffee shop that serves espresso drinks, cold brew in summer, pourovers, and batch brew, so they needed something nimble and crowd-pleasing. Gently bright, spice-toned and citrusy, this blend is both versatile and accessible.

Valkyrie (92) — yes, of Norse mythology — is Small Eyes Café’s everyday coffee, designed to be affordable and approachable. Honduras, Brazil and Ethiopia coffees combine for a cocoa-toned, floral cup. It’s not clear how the name intersects with the coffee, but it sure is catchy for those mainly in pursuit of caffeine. Owner/roaster Tom Chuang says he developed it for use as espresso, but it works well as a filter coffee, too.

Creative Originals

And then we have coffees that refuse to be tamed by convention. First among them is Old Soul’s Whiskey Dreams (94), named not for its barrel-aging (no, it’s not one of those) but for how the sweet ferment of the Ethiopia natural-processed component evokes whiskey. The other component, co-owner Jason Griest explains, is a Sumatra Adsenia Triple Pick imported by Royal Coffee, which, combined with the fruity Ethiopia Dur Feres G3 from Catalyst Trade, results in a fourth-wave mocha java (here spelled “moka java), the classic blend formula that traditionally combines a wet-hulled Indonesia coffee with a natural-processed Yemen. In addition to calling out his longtime importer-partners, Griest acknowledges his former roaster, Ryan Harden, and his current roaster, Brad Terry, for collaborating with him on the blend. He points out that “Components matter, importers and exporters matter, and roasters matter,” seconding the focus on traceability widely embraced in specialty coffee today.

Black Level Blend by St1 Cafe/Work Room in Tainan City, Taiwan. Courtesy of St1 Cafe.

New Tainan City, Taiwan roaster St1 Cafe, which operates a coffee shop and workspace, offers the Black Level Blend (94) comprised of coffees from Kenya and Colombia. Deep-toned and sweetly savory, it exhibits notes of cocoa nib, ripe tomato, lemon verbena, star jasmine, and cedar. Roaster Carrie Chang says the concept started with a two-Kenya blend used in a canned espresso martini, modified here to include a washed Colombia to tone down the Kenyas and contribute classic chocolate notes.

Another roaster that is flipping the script is Taiwan-based Fumi Coffee, whose First Love Blend (92) is what we at Coffee Review call a caveat coffee, meaning that not everyone will love it, but if you do, you really do. The most experimental coffee among the 10 we review here, it combines an Ethiopia natural-processed Uraga and a double-washed Kenya with a Colombia fermented in a specially prepared culture of yeasts, sugars and passionfruit. The result is an umami-fruit bomb. Roaster/owner Yu Chih Hao says he was going for a coffee not easily forgotten, and this intense cup fits that bill.

No matter how you brew, or what style of coffee you prefer, it’s high time to reconsider blends. The thoughtfulness and creativity going into house blends these days — in sourcing, combining, roasting, brewing, and naming — is playful, serious, historically relevant, precise, evocative — and, of course, delicious.

We hope you enjoy this full-circle trail from Coffee Review’s first report, published 25 years ago, to this account of the diverse, exciting house blends available today.