The three coffee-growing countries that range along the Andes south of Colombia — Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia — have rich and storied coffee histories. When Coffee Review last dove in to this region, with reports in 2010 and 2013, we found many impressively solid, softly balanced coffees in the Latin-American tradition — all produced from classic tree varieties like Typica and Caturra and processed with care by the time-honored washed or wet method. Coffees that stood out did so because of the purity of their traditional preparation and their balanced structure, not because of unusual tree variety, processing method or particularly original cup profile.

Although this month’s survey did turn up several very impressive coffees in that traditional mode, consider the following signs of change and experimentation in this region. Tree variety: Submissions for this year’s report included six Geishas, an expensive and distinctive variety of Arabica just beginning to be widely grown outside Panama (its most famous producer) and Ethiopia (its ancestral home), plus several samples produced from the newish Sidra variety (a hybrid of Typica and Bourbon). Or take processing method: 16 of the 48 coffees we tested for this month’s report were processed by the dried-in-the-whole-fruit or natural method, rather than the traditional washed method once completely dominant in the region.

David Pittman, of Peach Coffee Roasters in Atlanta, Georgia, updating his roast log. Courtesy of Peach Coffee.

For drinkers of specialty coffee, this experimentation seems to be paying off. Two of the Geishas (one wet-processed, one natural) and one Sidra (natural-processed) rose to the top of this month’s scorecard, as did two naturals produced from traditional tree varieties. These coffees joined several superb coffees of the classic style to fill out the 11 coffees we review here, rated 93 to 91. And although this ratings range is narrow, the breadth of nuance in aroma, structure, body and flavor runs the whole sensory gamut.

The Fair-Trade/Organic Conundrum

Peru, in particular, has long been a go-to origin for organic and fair trade-certified coffees. For our 2013 report, more than 60% of the Andes coffees we tested were certified organic, and almost 50% were fair trade-certified. By comparison, for this month’s report only eight (about 17%) of the 48 coffees submitted were labeled fair trade and/or organic (FTO). Perhaps such certifications are less meaningful now to consumers than they were in previous years, or roasters no longer feel that offering certified organic and/or fair trade coffees is worth the effort and money involved. Keep in mind that, even if U.S. or Canadian roasters buy organic-certified green coffee, they cannot print “organic” on the label and use an organic seal unless their roasting facilities are also certified for handling organic coffees, a demanding and time-consuming process. Similarly, exhibiting a fair trade seal on a coffee requires a licensing partnership, which also involves money, time and oversight. (See our report on fair trade-certified coffees.)

Probably for these reasons roasters may buy a coffee certified fair trade/organic but may choose not to take the steps necessary to legally display the certification seal. Apparently, this was the case with more than 10 of the submissions we spot-checked among the 48 samples we received. In other words, even though a bag was not labeled as FTO, a quick search online of the importer’s site indicated that the green coffee was certified at origin. So, the farmer is still getting a certification premium at the farm level, but roasters are choosing not to take advantage of this ethical appeal in their marketing.

The Direct Trade Alternative

Several roasters I spoke with for this report speculated, off-the-record, that farmers now need to differentiate their coffees more by way of intrinsic cup quality and distinction than by certification. So, in some cases, the value added by certification has given way to the more personalized appeal of direct trade, a set of practices that are not formalized, but are increasing in popularity as a new way for farmers to add value to their coffees: roasters, often dealing directly with producers, pay more for small lots of very distinctive-tasting coffees. Farmers often can earn more for a direct trade coffee with distinctive cup character created in collaboration with a roaster than they can through producing a possibly less-distinctive certified coffee. Of course, the value-added in direct trade is fluid and negotiable (as is the premium paid for organic certification). Only fair trade stipulates a formula-determined minimum price.

Miguel Meza, of Paradise Coffee Roasters, with Guillermo Ortiz, owner of Finca Victoria, in the Pichincha Province of North-central Ecuador. Courtesy of Miguel Meza.

We spoke with Melissa Wilson and Parker Townley of Fair Trade USA (whose global seal reads Fair Trade Certified) to try to understand some of the nuances of this complex situation. Townley points out that the fair trade premium paid to producers, which is a significant $.20 per pound, enables coffee communities to undertake important social projects involving such necessities as cancer screenings, nutrition initiatives, education, and food security. He says, “It also positions them to deal with crises like rust, by being able to direct the premium to renovation, without waiting for governments or international development agencies to get some help; or the coffee price crisis, by being able to pay part of the premium in cash and supplement farmer incomes. The premium also enables farmers to grow in capacity by investing in things like cupping labs, dry mills, and staff training.”

Wilson adds that, while many farms are organic by default — because farmers don’t have access to affordable agrochemicals — the Peruvian government (along with other countries like Mexico) — has supported large-scale organic certification to add value, and the combined fair trade/organic premium on these coffees is $.30 a pound. And she says, “Fair Trade is a base supporting a lot of different initiatives that help farming communities. It does not pretend to be a magic wand to solve all problems, but it gives producers a very important range of motion, and sets the stage for efforts to be built upon.”

The roasting room at Peach Coffee in Atlanta, Georgia. Courtesy of Peach Coffee.

David Pittman of Peach Coffee Roasters in Atlanta, Georgia, whose Natural Utcubamba we rated 91, says that, for better or worse, his customers don’t have FTO on their radar. “Currently, we are the only specialty coffee shop within a five-mile radius,” he says. “We are in the introductory phase of specialty coffee with our customers. For the most part, we have about 15-20 seconds to explain what sets our coffee apart from commodity. To try to explain FTO might be a bridge too far for us, right now.” He bought the wildly unusual natural-processed Utcubamba simply because he loved how it tasted. We read notes of caramelized banana, hibiscus, cedar, pipe tobacco and rum cordial — not a coffee you’d pin as a Peru in a blind-cupping. Even though this coffee isn’t labeled fair trade, its purchase supports farmers on the ground by way of the fair trade premium.

Similarly, Nathan Westwick of Wild Goose Coffee Roasters in Redlands, California submitted a lovely Peru Chirinois San Ignacio (92) that is certified organic at origin, but since the roastery isn’t also certified, he isn’t able to promote the coffee as such. Ideally, the consumer ought to know about the certification, too, but at least the farmers are being rewarded for producing coffees in ways that Wilson says are “better for the farmer and for the planet.”

Wild Goose’s Peru Chirinois. Courtesy of Wild Goose Coffee Roasters.

The Sensory Experience, From Classic to Experimental

Of the 11 coffees we review here, some were sensory rides as wild as the Peach Coffee Utcubamba. Bird Rock’s Finca Tasta Peru (93), a natural-processed Red Caturra, offered up blood orange zest, dried raspberry, ginger blossom, cocoa powder and sandalwood — again, not your classic Peru cup, which is typically balanced, soft in structure and understated in aromatics. Of this coffee, Maritza Suarez-Taylor of Bird Rock says, “[Farmer] Edith Meza started to experiment with honey and natural-process coffees in 2014, and after tasting a lot of samples, we offered the first coffees from this process in 2016 (at PT’s Coffee, a brand also owned by Suarez-Taylor and her husband, Jeff). Every year, Edith and her brother Ivan ask for our feedback on what they can do to improve the green coffee, which is a challenge for them due the lack of infrastructure and knowledge in coffee processing that deviates from the traditional washed process. For this coffee, we asked her to separate out the Red Caturra. Each year we continue to see improvements in quality and consistency.”

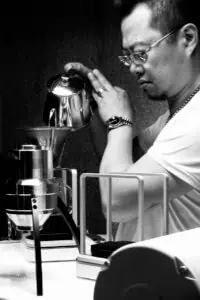

Sean Tung of Sucré Beans in Taipei.

Other experimental coffees we review include three produced from the Geisha variety: Taiwan-based Sucré Beans Bolivia Yungas Caranavi Alasitas Geisha Natural (93), whose spice-toned, delicately fruity profile wooed us; a second natural Geisha from the Caranavi region of Bolivia by Plat Coffee in Hong Kong (91), with a more reserved, cocoa-toned presentation; and a washed Blues Brew Geisha Pasco Oxapampa Peru (92), also roasted in Taiwan, alive with resonant floral and deep candied nut tones.

Blues Chen of Blues Brew in Taipei.

In the classic wet-processed camp, Minnesota’s Paradise Roasters Ecuador Pichincha Typica (93), a version of which made our list of the Top 30 Coffees of the Year in 2018, leads the way with its richly sweet-savory notes of cocoa nib, mango, lemon verbena and freesia. Kansas-based PT’s Coffee’s washed-process Sidra (the Typica-Bourbon hybrid) landed at 93 for its rich-toned, engaging complexity, more like a “classic” cup in Technicolor.

A Cajamarca Peru from Greater Goods Roasting in Austin, Texas and an Ecuador Finca La Papaya (92) from Willoughby’s Coffee & Tea in Branford, Connecticut, both conventionally wet-processed, each earned 93 points for their straight-ahead flying of the classic flag. The former is deeply rich and sweetly savory, while the latter is crisply tart, more citrus-driven.

The Ecuador Los Eucaliptos from Kickapoo Coffee (93) in Driftless, Wisconsin reads a bit like a clean but idiosyncratic natural-processed coffee with its notes of very ripe plum and root beer, but it turned out to be a washed coffee whose roast profile also showed off its pretty fruit and sweet herbaceousness.

The Current State of Andes Coffees

Many farmers in this region are recovering from one of the worst outbreaks in history of the devastating coffee fungus known as leaf rust. Several roasters I spoke with suggested anecdotally that the need for re-planting is one explanation for the experiments with varieties such as Geisha and Sidra, as these coffees command higher prices than Typica and Caturra. Experimental processing methods, on the other hand, are almost certainly driven by market demand for distinctive-tasting coffees. There is a growing desire, especially in Asia, the U.S. and Canadian markets, for the unusual, often fruit-driven character of natural-processed coffees. Sean Tung, of Sucré Beans in Taipei, says he thinks processing experiments are also going global by way of producers sharing information across continents.

Shihpan (James) Chuang, of Taipei-based importer Pebble Coffee, cautions that, with the pursuit of naturals in producing regions that don’t have traditions of this processing method, the proposition can be especially risky. But he agrees that producers can ask more for these coffees, given their potentially unique profiles and the additional labor and time required to produce them.

Amy Broderick, a trader with Olam Specialty Coffee, puts an even finer point on it: “The possibility of inconsistent results is higher than with washed coffees, and over-fermentation is common. The process can be piloted, but then once the farmer nails it in small batches and moves on to larger quantities it’s possible they run into factors they can’t control (too high temperatures, too much rain, etc.), and if something small turns into something big in the cup quality, they’ve risked it all for nothing.

“Beyond that,” Broderick continues, “not every farm can take on the risk of experimentation. With a market that fluctuates the way we’ve been seeing, just having the capital to invest in innovating products is often not an option, especially knowing that some of those experiments will not yield perfect results in the short term. It could take a few harvests to really pinpoint the perfect cup for that region and variety. If farmers don’t have partners on the ground who can cue them in to the information and feedback they need, then the risk could be considered too high.”

In fact, over-fermentation was the most common issue with the natural-processed coffees we cupped that did not score high enough to be included in this report.

While it’s impossible to know how the experimentation going on in this region will ultimately play out, our cupping of 48 coffees from Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia, with their exhilarating mix of profiles both classic and unorthodox, appears to bode well for the future.