At Coffee Review, we often feel conflicting impulses and pressures in regard to coffee retail prices. On one hand, we feel strongly that high retail prices are essential to support producers as well as to honor our commitment to coffee as an extraordinary beverage. On the other, we want to be inclusive and recognize that many readers may not choose to pay a premium for brilliant microlot coffees. Coffee has a long and honorable history in the U.S as an accessible beverage, a luxury available to everyone. So we also feel obligated to try to find outstanding coffees at affordable prices, even though that obligation may in part run counter to our commitment to the producer and to coffee as a price-is-no-issue art form.

A close-up look at Crescendo Coffee’s roasting operation in Yongin-Si, South Korea. Courtesy of Crescendo Coffee.

Hence the topic of this month’s report: a search for outstanding specialty coffees at everyday prices. First, however, we had to figure out what constitutes an “everyday” price for a fine coffee. After some poking around, we settled on a price of less than $15 per 12 ounces. To put that price point in perspective: Only four of the coffees we recognized in our Top 30 Coffees of 2017 sold for less than $15 per 12 ounces. True, half of the coffees on that 2017 list sold for under $19 per 12 ounces, still a very attractive price for such exceptional coffees, but the rest sold for significantly more—as dauntingly high as $206 per 12 ounces.

44 Samples at Less than $15

In our pursuit of fine but affordable specialty coffees, we tested 44 samples from 28 roasters in North America and East Asia, all currently selling at a regular (non-sale) price of $15 or less per 12 ounces.

What did we find? We found, for starters, three extraordinary 94-rated coffees that fulfilled our price criterion, plus seven more that we rated 92 to 93. All 10 of these 92- through 94-rated coffees are reviewed here. Many of the other 34 samples were solid, though not distinctive, in the general style that we usually rate between 86 and 89. Others we rated 90 to 91, excellent scores, though not quite high enough to make the cut for our report. Reassuringly, only a handful of the coffees we tested displayed signs of tainted or faded green coffees, the sign of cutting corners on cost.

10 at the Top

The 94-rated Allegro Three Queens Blend is an all-Africa blend that cunningly layers coffees from Ethiopia, Burundi and Kenya. It is crisp yet lush, deeply savory yet lyrically sweet. Like many of the fine blends we have reviewed in recent years, it appears not to be aimed at cutting costs or imposing predictability, but at creating an original coffee experience that has never existed in quite the same way before.

The remaining nine samples at the top of this month’s ratings are all single-origin coffees rather than blends, although they tend in general not to be special microlot selections produced from unusual tree varieties or subjected to atypical processing methods. Rather, they appear to be distinguished versions of classic coffee types associated with their origins. They could be taken as triumphs of the best and most caring in the specialty coffee supply chain, rather than brilliantly crafted exceptions to the classic, as is often the case with coffees that achieve high ratings at Coffee Review.

The Classic Prevails

The classic description clearly applies to the other two 94-rated coffees that top this month’s ratings, the Big Shoulders Kenya and Klatch Coffee Sumatra Mutu Batak. The Big Shoulders coffee is a fine Kenya through-and-through, simultaneously typical and exceptional, a resonant fusing of juicy-floral sweetness and layered zesty, gingery depth. The Klatch Sumatra similarly is classic for its type. It displays, among other sensory features, a refined version of the flavor complex that gave Sumatra its reputation for earthiness. Many of the finest Sumatras we cup are not earthy at all, but this one is alive with the sort of heady freshness that rises from shuffling through moist, just-fallen leaves. The pungent grapefruity citrus and dark chocolate are further classic signs of a fine traditional, wet-hulled Sumatra.

We found other classic profiles among the 92- to 93-rated selections: Two excellent variations on the classic wet-processed style of southern Ethiopia (the Caffeic Ethiopia at 93 and Java Blend Ethiopia Reko at 92) joined one slightly unorthodox Ethiopia, a white-honey processed Guji (93) from Kakalove Café in Taiwan.

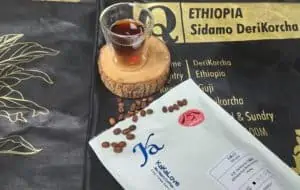

Kakalove Cafe’s Ethiopia Guji DeriKorcha Honey, one of the Value Coffees featured in this report. Courtesy of Echo Liu.

Two impressive and characteristic Central Africa profiles included a spicy, sweet-savory Congo Kivu from Grounds for Change (92) and a typically bright yet brothy, big-bodied Rwanda from Mr. Espresso (92). Crescendo Coffee Roaster’s Nicaragua (also 92) offered an engaging variation on the sweet, plump, gently tart profile often associated with that origin.

The Price/Distinction Trade-Off

How did roasters of these high-rated coffees achieve such an impressive balance of distinction and affordable price? In part, it appears, through buying quality coffees of traditional types produced in some quantity and well-curated all along the supply chain. Also, it appears, by running a tight ship at home. We saw very little sign of fancy packaging, showy graphics, or marketing effusions among the coffees lined up on our lab counters for this cupping.

Terraced drying beds in Kalehe, South Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Courtesy of Grounds for Change.

Kelsey Marshall, co-founder of Grounds for Change, the roaster of the fine Congo Kivu reviewed at 92, writes that his company “has always striven to provide the highest quality fair grade organic coffee … at the best price possible. That means fine-tuning our operations and being very mindful about how we operate our business.” Scott Bouma, co-owner with his wife Rayna Bouma of Caffeic Coffee, attributes his company’s modest prices in part to “keeping facility overhead low; doing as much work as feasible in-house; and focusing on quality product rather than large marketing budgets.”

Coffee Prices in the Big Picture

Despite the good news of this month’s cupping, we need to recognize that, seen in the larger global picture, coffee production and coffee producers are in a serious economic jam. In the past 20 years the basic price paid to growers for a decent-quality green Arabica coffee has decreased, not increased. Decreased rather radically. In 1997 the composite price for an unroasted Arabica coffee in the “mild” commodity category, meaning a cleanly processed, good quality coffee, was $1.89 per pound. In 2017, 20 years later, the composite price for the same category of good-quality unroasted Arabica coffee was $1.59 per pound. Both figures are taken from statistics published by the International Coffee Organization (ICO).

Furthermore, if we apply the average global inflation rate of 3% per year, a consensus figure, to that original composite price of $1.89 achieved 20 years ago, coffee growers supplying the same basic quality of coffee in 2017 should have received an inflation-adjusted price of $3.41 per pound.

They did not. In fact, they got less for their coffee than they did 20 years ago. Considerably less. It appears that, in the big picture, consumers are paying more for coffee and valuing it more, while producers, most of them at any rate, are getting paid less than ever for it.

The Relentlessness of Commodity

One way of looking at this contradiction is that the world commodity system as it applies to mainstream coffee is so entrenched, so relentless in its emphasis on price alone throughout the supply chain, that coffee quality, the environment, and the lives and souls of the small-holders who produce most of the world’s coffee are continuously and repeatedly crushed.

Somehow the coffee commodity system seems able to shrug off continued efforts to effect long-term change through certification schemes, development programs, and many other vigorously pursued and well-intentioned initiatives. This depressing picture, so far as I can see, remains the basic reality of the larger global coffee industry today.

Working Around the System

Specialty roasters like those represented in this article, and others like them, are well aware of this paradox. They do their best to transcend it, to pay more to producers for their very best and most distinctive coffees, to celebrate coffee producers as co-creators, and often to contribute to various coffeelands development efforts. They also try to offer extraordinary microlots of expensive coffees that represent coffee at its peak as collaborative art form, yet at the same time do their best to satisfy their customers’ need for quality coffees at affordable prices.

Gathering reliable statistics on how much more producers are paid for specialty coffees as opposed to coffees bought through the commodity system is difficult, but a group of researchers reporting on Transparent Trade Coffee (TTC) has over the past two years gathered statistics from a basket of participating specialty roasters aimed at understanding the actual pricing practices of the specialty coffee supply chain. Although the scope of the sampling is small and the participants self-selected, the methodology and definitions on the TTC site appear sound. Taking into account 77 specialty coffee transactions registered in 2016, the average price paid for these 77 specialty green coffees at the point they were waiting to be transported out of the origin country (FOB or Free on Board) was $3.81. The comparable figure, also FOB, for a good quality Arabica coffee as reported by the ICO statistics cited earlier for the same harvest year (2016), was $1.64 per pound.

If we take these two figures at face value, then the specialty coffee system paid $2.17 or 132% per pound more for what we may assume was better quality and more distinctive green coffee. Skeptics may, quite justifiably, point out weaknesses in the details of that comparison, including the small sample of transactions on the specialty side, but the TTC researchers appear to have been careful in interpreting their data. The TTC statistic was arrived at, for example, after excluding what the authors called “outliers,” coffees like microlots of the Gesha variety that invariably sell for extremely high prices and tend to distort overall statistics on green coffee costs.

Of course, small microlot coffees, coffees bought at auction, coffees that have won prizes as green coffees, not to mention coffees from rare tree varieties like Gesha, all net considerably higher prices (and more prestige) for producers. But it does appear that even traditional, modestly priced specialty coffees like those we review this month generate better returns than the commodity norm for those involved in their production.

Going for Balance

In regard to striking a balance between pressures to offer more distinctive coffees and pay producers more while still satisfying the need to attract customers and stay solvent, Mike Perry of Klatch Coffee sends a wonderfully comprehensive response. “At Klatch we buy the best coffee we can, but recognize that not everyone can afford to drink Geisha, for example, every day. So we balance quality and value with what we call sustainability.”

He continues: “This sustainability begins with rewarding the farmer by paying a fair price based on quality, a fair price that allows the farmer to maintain a quality product year after year. But that sustainability has to continue as a fair price to us, the roaster, so we can be profitable to invest in our company and people and be able to maintain quality year after year. And finally that sustainability and fair price has to be supported by the consumer and end user so they can enjoy quality coffee day by day. So, as buyers of quality coffee, our goal is not just to buy the most expensive coffee, but to buy the best coffee at a value that provides sustainability to the farmer, to us as a roaster, and to the consumer.”